Harry Pieris was born on 10th August 1904, the eighth of eleven children, one of whom died at an early age. The remaining ten, six boys and four girls, were a rather motley crowd, in that they had widely differing tastes and attitudes to life. Harry was the only one who liked art enough to actively pursue it throughout his life. But they all shared a love of animals and fresh tasty food! He ate with feeling and said that was how food should be eaten. Not for him mass produced fast food or food guzzled in a hurry. He was reluctant to visit restaurants but I did persuade him once. “This food is not absolutely fresh nor is it cooked with love so it will not properly nourish you” said he.

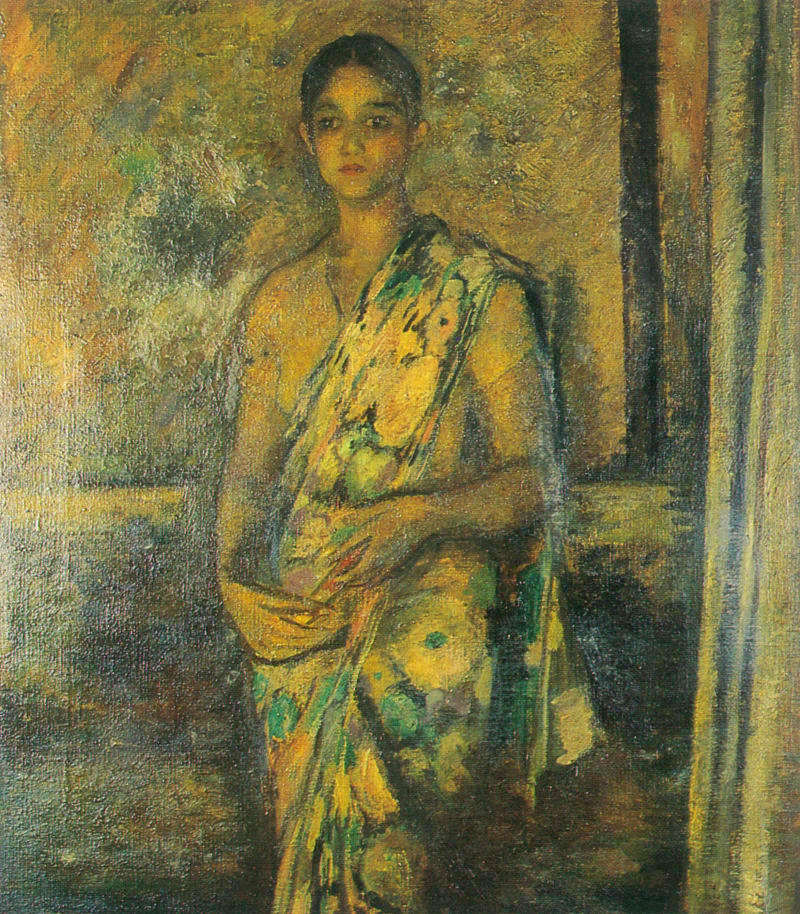

He enrolled at Mudaliyar A C G S Amerasekere’s Atelier School of Art as a youngster. Justin Daraniyagala was another student there. The good Mudaliyar was a skillful artist but had a rigid and academic approach to art. Eventually realising that Harry would benefit from more tutoring, he suggested to his parents that he be sent abroad for further studies. So it was that in 1923 at the age of 19 he joined the Royal Academy in London, whose Principal at the time was Sir William Rothenstein. Apparently he preferred the Royal Academy to the Slade School of Art because he liked their attractive cerise pink gown. Sir William was the first to recognise Harry’s talent for portraiture and encouraged him in that direction. In 1926 he won the prize for the best portrait, one of his uncle, Sir James Pieris. In 1927 he obtained the diploma of the College. The many portraits he did during his life which are on view here will bear witness to his great ability to capture not only the likeness but the character, not always flattering, of his sitters.

Many sitters who commissioned him, paid for the portraits and gave them back to him because they weren’t made pretty enough! Our gain – their loss as I hope you’ll agree during our Gallery Walk later on.

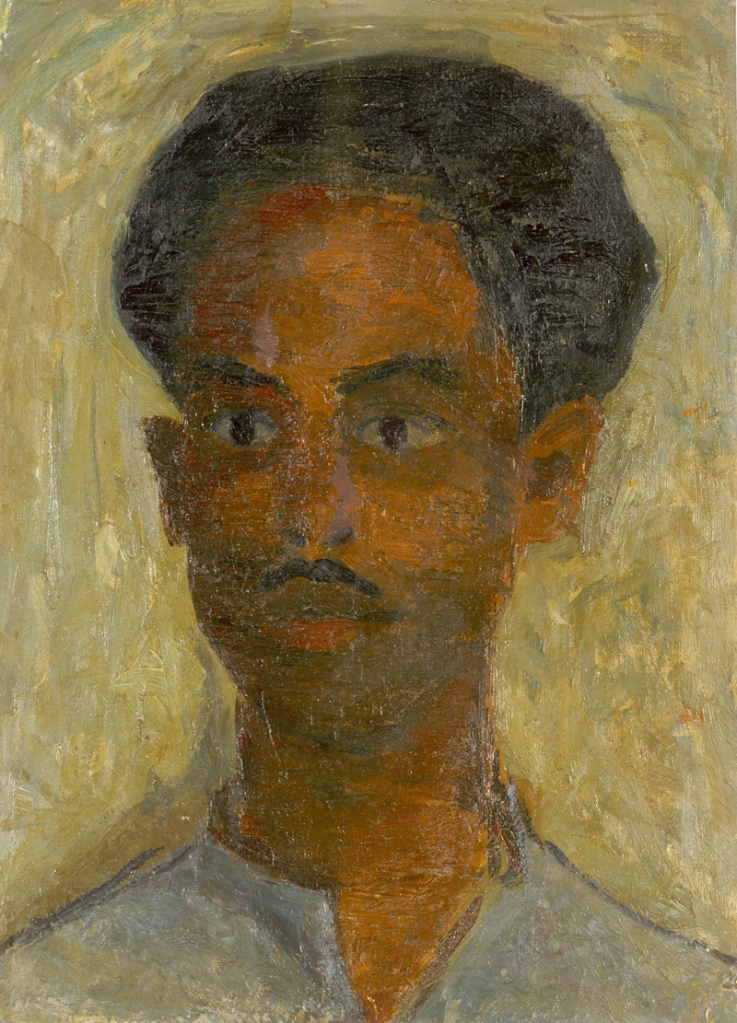

He returned to Ceylon and was here from 1927 to 1929 before going to Paris, following Rothenstein’s advice. He spent six years there under the tutelage of Robert Falk, who encouraged him to copy the old masters in the numerous Parisian galleries to further his skill. One such copy, a nude after Rembrandt, is on display here. Also to be seen is a painting of the young Harry by Robert Falk, in a somewhat early- Picasso-like style. Another of Falk’s students, a Rumanian lady Luiba Popesco, described as a woman of great intelligence, integrity and charm, became a close friend of his. Some of her paintings too are here on display.

Paris at the time was a hub of artistic activity. Picasso, Matisse, Braque, Roualt, Leger were some of the artists there while Ravel and Stravinsky were writing music. It was a very stimulating place for one of artistic bent. Harry was particularly close to Matisse and his family, whose hospitality he enjoyed. Harry worked at the Atelier de la Chaumiere and two small galleries during his time in Paris. Justin Daraniyagala, too, studied art in Europe and the two met frequently in Paris and London. He attended meetings of the Friends of Tagore Institute in Paris and decided to offer his services to Tagore’s Abode of Peace in Shanthiniketan in India. He was recommended for this post by Sir William Rothenstein and he worked there for two and a half years, before returning to Ceylon in 1935 at the age of 34.

He then looked after his family’s agricultural and other properties, developing an abiding interest in agriculture and gardening. The beautiful gardens of the Sapumal Foundation bear witness to this, though it must be said that during his lifetime the gardens were even more beautiful. He read widely and was interested in philosophy, theosophy, literature, poetry, temple paintings and rather anti-colonial and left leaning politics. He was a person of simple elegance with an eye for beauty, who mixed happily and learnt from people of all creeds, races, classes and backgrounds. He lived by the ideal propounded by Ananda Coomaraswamy, “Nations are made by artists and poets, not by traders and politicians. Art contains in itself the deepest principles of life, the truest guide to the greatest art, the art of living”. He believed like Coomaraswamy, that the artist was not a special kind of man but every man or woman was a special kind of artist. Good work, whether painting, making pottery or food was a love affair between the artist and his production, done with feeling.

He was a man who was content with what he has – a rich man in the eastern sense, which holds that a rich man is not one who has a vast fortune but a man who is happy with what he has.

Art which is truly great has endured over the centuries even though unsigned by the artists who did them. Will the art of these days prove to have the same qualities? Time will tell.

His understanding of art was further enhanced by a visit to the USA in 1953 and a visit to China in 1957.

He was also a teacher of art, who always encouraged young people to follow their inclinations. As Ian Goonetilleke wrote, “He provided the stimulus for others to forage more audaciously than he was inclined to do. He also had the intelligence and percipience to realise that other artists were unable to remain indifferent to the new manifestations of social and cultural change set in motion by the forces of independence, nationalism and socialism. Within his chosen limitations he strove to appreciate the new aesthetic urges, even if he may not have understood the reasons for their emergence in a larger society. He tried to identify and encourage these tendencies when he discerned that the creative talent was present. ”

Harry Pieris lived, studied, and worked in Europe for almost a decade in his formative years, and his inspiration owes a great deal to this influence. But his later stay in India, and his long familiarity and studious knowledge of the best elements and styles in the Indian and Sri Lankan traditions of painting and sculpture, both classical and folk made their congenial impress on his aesthetic sensibilities.

He was an early admirer and publicist of the better forms of religious art, and would speak with undiluted enthusiasm of certain little-known, Buddhist fresco paintings in Southern temples. But it is time to look a little more closely at his progress at the easel before concluding this brief evaluation of his art and times.

As with nearly all Ceylonese painters, of that time and later, he first studied at the Atelier School of Art conducted by the formidable A. C. G. S. Amarasekera, but the true and enduring foundations of his art were laid at the Royal College of Art, London, where he won his spurs and a diploma under William Rothenstein in 1927.

was inspired by Ananda Coomaraswamy’s ideal that, “Nations are made by artists and poets, not by traders and politicians. Art contains in itself the deepest principles of life, the truest guide to the greatest art, the art of living” and his life laid testament to this. Harry Pieris studied at the Atelier School of Art in Colombo and then went on to the Royal College of Art where his portrait of his uncle, Sir James Pieris won the best portrait award for that year.

After a brief stint back in Colombo, he worked and studied in Paris for six years and then worked in Shanthi Niketan, India for two years.Matisse and Henri Cartier-Bresson were among the many friends he made during his time abroad and his years in Paris and India

greatly influenced his art. Believing that good art was a love affair between the artist and his work, he worked towards the promotion of the arts and was committed to being a teacher. Upon his death, the house was discovered to be teeming with a profusion of artwork – from pencil sketches stuffed in drawers and crevices to canvases rolled and stored in corners.

After the death of Lionel Wendt in 1944, it was Harry Pieris who became the driving force behind the ’43 Group. His mother’s house became the new meeting place for the Group and he functioned as the Group’s first and last secretary. The founder members of the ’43 Group were Lionel Wendt, Geoffry Beling, Harry Pieris, Richard Gabriel, Ivan Peries, George Keyt, George Claessen, Aubrey Collette, Justin Daraniyagala and Ven. Manjusri Thera and a considerable part of the work on display at the Sapumal gallery consists of these original members who were crucial in sculpting the face of contemporary Sri Lankan art. Other familiar names include Stanley Kirinde, Marie Alles Fernando, Chandramani Thenuwara and Swanee Jayawardene. Most of the works on display consist of Harry’s own personal collection (some he personally acquired and some, gifts) while there are a few private collections which are on loan to the foundation.

Bevis Bawa’s pithy caricatures of figures such as Martin Wickremasinghe (the writer is depicted holding a large quill and sports a glum expression and spectacularly large forehead), Sir John Kotelawala, Sir Razik Fareed, Col. C.P. Jayawardena and Badurdeen Mohamed are worth perusing closely. The variations in Keyt’s style are discernible through his work spanning seven decades. With their trademark enlarged eyes, bold lines and distinct aquiline noses, while browsing his work you’ll notice that Keyt’s figures contain what Pablo Neruda described as, “a strange expressive grandeur, and radiate an aura of intensely profound feeling”. Lionel Wendt’s black

and white photographs catch your eye and Ven. Manjusri Thera’s faded copies of temple murals contain kings, courts, conch blowers, musicians and demons distilled from jathaka katha.

Rohan de Soysa, Chairman of the Sapumal Foundation, is a veritable wellspring of art anecdotes and the stories embedded inside the Sapumal Foundation. Not only of its founder but of the artists displayed within and of the love affairs, histories and feuds of those immortalized in paint, pencil, turpentine and canvas. Seevali Ilangasinghe, a self-taught painter from Kekirawa, trekked to Colombo and earned a living by selling his drawings on scraps of paper (while browsing, do keep a look out for Seevali’s paintings on the doors of one of the rooms – an interesting example of taking a pragmatic object and infusing it with a touch of visual poetry). Beginning his career as an Art Master at Royal College, Aubrey Collette’s caricatures were roguishly accurate and a cursory browsing of his political cartoons reveals relevance even today. Once, having offended the Bandaranaikes with one of his cartoons, he promptly responded by irreverently doing another. Harry Pieris, a master portraitist, tried to capture the character and essence of his subjects instead of merely flattering them and often portraits commissioned were indignantly returned to him.

Upon his death, Harry’s house and garden, vast art collection, artefacts, furniture and library were bequeathed to the Foundation. Sapumal was incidentally a nickname bestowed on Harry – the flower of the Sapu tree never blooms in full and the implication was that Harry like the flower, never quite completely matured.

The house (formerly three workmen’s cottages, now converted to a bungalow) and gardens have been described by Harry’s friends, as an extension of Harry, himself. While it would be too simplistic to draw direct parallels, the high ceilings, garden filled with bougainvillaea and anthuriums, modest furniture, carefully selected curios and ample lighting in the house are subtle indicators to the artist’s simplicity and love for beauty. “Harry was a very simple man. He had a car to get from place to place but he didn’t want the latest model. He liked music but didn’t get the highest priced or highest quality music sets. Those things didn’t matter much to him. But having around him what was beautiful or what he considered beautiful – that was important,” Rohan muses.

Keeping a box of Harry’s paints and assorted clutter as well as a tin of brushes with dusty bristles in the studio, is an interesting touch and augments the aura of suspended time that is an integral part of the Foundation’s charm. It takes very little coaxing of the imagination to envisage the Sunday tea-time salons that Harry hosted, with topics ranging from philosophy, sociology, art and politics being spiritedly discussed over tea and sandwiches. “Somebody threw off an idea and others picked it up,” reminisces Rohan who had attended a few of the Sunday salons before he was a trustee of the foundation.

The Foundation celebrates its 40th year this year and its location consists of the house which contains the main gallery and permanent collection, a space available for exhibitions, a reference library and an archive of newspaper cuttings and catalogues on the ’43 Group and twentieth century artists of Sri Lanka. An auxiliary gallery which displays the work of Varuni Hunt and a studio apartment which is rented out to visiting artists are also on the premises. Children’s art classes are conducted by Noeline Fernando while the adults’ classes are conducted by Professor Sarath Chandrajeewa at the art studio.

With squirrels scuttling away with scraps of Keyt’s, Daraniyagala’s and Ivan Peris’ works for their nests, maintaining a building more than a century old, battling the decay that time wreaks on art as well as storing, preserving and restoring over 700 works of art (part on display and others in storage) ensures that the work of the Sapumal Foundation is a continuous process. “Time takes its toll. We restore things and keep the place as best as we can. We don’t go overboard – within our means, we do the best we can,” explains Rohan adding that the Foundation also provides sponsorship or financial support for artistic endeavours whenever possible.

As Rohan points out, its uniqueness lies in the fact that it is a collection of artists by an artist and that the work displayed is an integral part of our art history but why else should people visit the Sapumal Foundation “It’s a tranquil place to visit. There’s a lot of beauty in the place and in the paintings that are on display as well as other artefacts. And I think people who come here will hopefully be refreshed by the experience,” smiles Rohan, “It’s not just about the paintings it’s a certain way of life and of what life could be like.”